A Masterclass in Deconstructing True Crime: Review of ‘Penance’ by Eliza Clark

In her second novel, Eliza Clark expertly marries form and content to create a challenging and compelling critique of the true crime industry.

This post is a (very slightly edited version of) a review I wrote in January of this year, for a blog I kept as part of my MA.

Eliza Clark’s 2023 novel Penance is unlike anything I’ve read before. In the novel, Clark employs the framing device of a true crime journalist’s non-fiction book about the murder of a teenager by three of her classmates. While the reader reads a book that Clark has constructed, within the world of the text, they are also reading a book that has been constructed by the journalist, Alec Z. Carelli. Through both form and content, Clark critiques the true crime industry and the way it tells and trivialises stories about murder, victims, and perpetrators, to a society that has become desensitised to them.

The reader is always aware of Penance’s framing device – that the narrative they are reading is a book written by a journalist who has fallen from grace, who intends for this book to earn him both a lot of money and his reputation back. Thus, this story has been crafted very carefully, with a specific audience and intention, and has been constructed and sensationalised accordingly. The book’s preface informs the reader that Carelli’s book was pulled from the shelves soon after its publication, after his interviewees accused him of misrepresenting them and it emerged that he had illegally obtained writings by two of the murderers from their time in prison. This preface ensures that the reader constantly questions what they are reading: what is true, and what has been exaggerated or fabricated by Carelli? This story has been written to emphasise the darkest and most disturbing aspects of the crime and its characters’ lives, raising the question: why are we as a society so fascinated by true crime? What do we want to take away from these stories? Carelli perhaps believes that his readers want to achieve some catharsis by reading about these horrific events in great detail. Clark, on the other hand, may believe the same, but she likely also thinks that her readers will engage more deeply with the text – the frame narrative will make them question themselves, and ponder this exact question.

Clark skilfully explores questions of subjectivity in the novel. The first part of the book explains Joni’s murder and briefly discusses her life, her family’s trauma in the aftermath of her death, and the murder’s context: the small seaside town of Crow-on-Sea and the 2016 Brexit referendum. The remainder of the book is split into four sections, which tell the story from the perspective of the three murderers – Angelica, Violet, and Dolly – and Jayde, a friend of the murderers who was falsely believed to be involved. Each section is composed of interviews with people who knew the subject, as Carelli tries to create an image of their lives before the murder and to understand why they did it. After each section, there is a prose piece wherein Carelli, from the third-person omniscient perspective of the perpetrator examined in that section, imagines how a particular event leading up to the murder may occurred. Carelli takes the characters’ voices and subjectivity away from them; he tells these important parts of the story in his own words, imagining rather than reporting. These prose sections are key parts of Clark’s critique of the true crime industry: she criticises how true crime writers tend to exaggerate and sensationalise, to tell a story rather than accurately report the facts of the crime.

Even though Carelli claims at the beginning to care deeply about Joni and to tell the true story of what happened to her, as the book progresses, it becomes clear that it is not about Joni. Carelli, like so many other true crime writers, podcasters, and video essayists, makes the story about the perpetrator rather than the victim. He is fascinated by Angelica, Violet, and Dolly, and why they committed such a horrific crime. But Clark herself is clever enough not to give an easy answer to this question. For each perpetrator, she includes multiple possible, simplified explanations for how they became the kinds of people who would torture their peer (and in Violet’s case, friend) and set her on fire: bullying, childhood sexual abuse, a difficult family life, the influence of the Internet and its dangerous sub-cultures, and peer pressure. It reminds me of Gus Van Sant’s 2003 school shooting film Elephant, which similarly provides many “reasons” for why a teenager would do something so brutal – and thus, provides no reason for it. Clark also cleverly writes the character of Joni. She is in no way the trope of the “perfect victim” used so often in true crime tellings of events – someone kind and caring who did nothing wrong and yet was the victim of a crime. Joni is often cruel, including to Angelica and Violet – because she is a teenager. By writing Joni as an ordinary teenager, with a lack of empathy and a capacity for cruelty, Clark criticises the trope of the “perfect victim”, because it implies the existence of an “imperfect victim”, someone who deserved what happened to them. You could argue that Joni provoked Angelica, Violet, and Dolly, but that could never justify her murder.

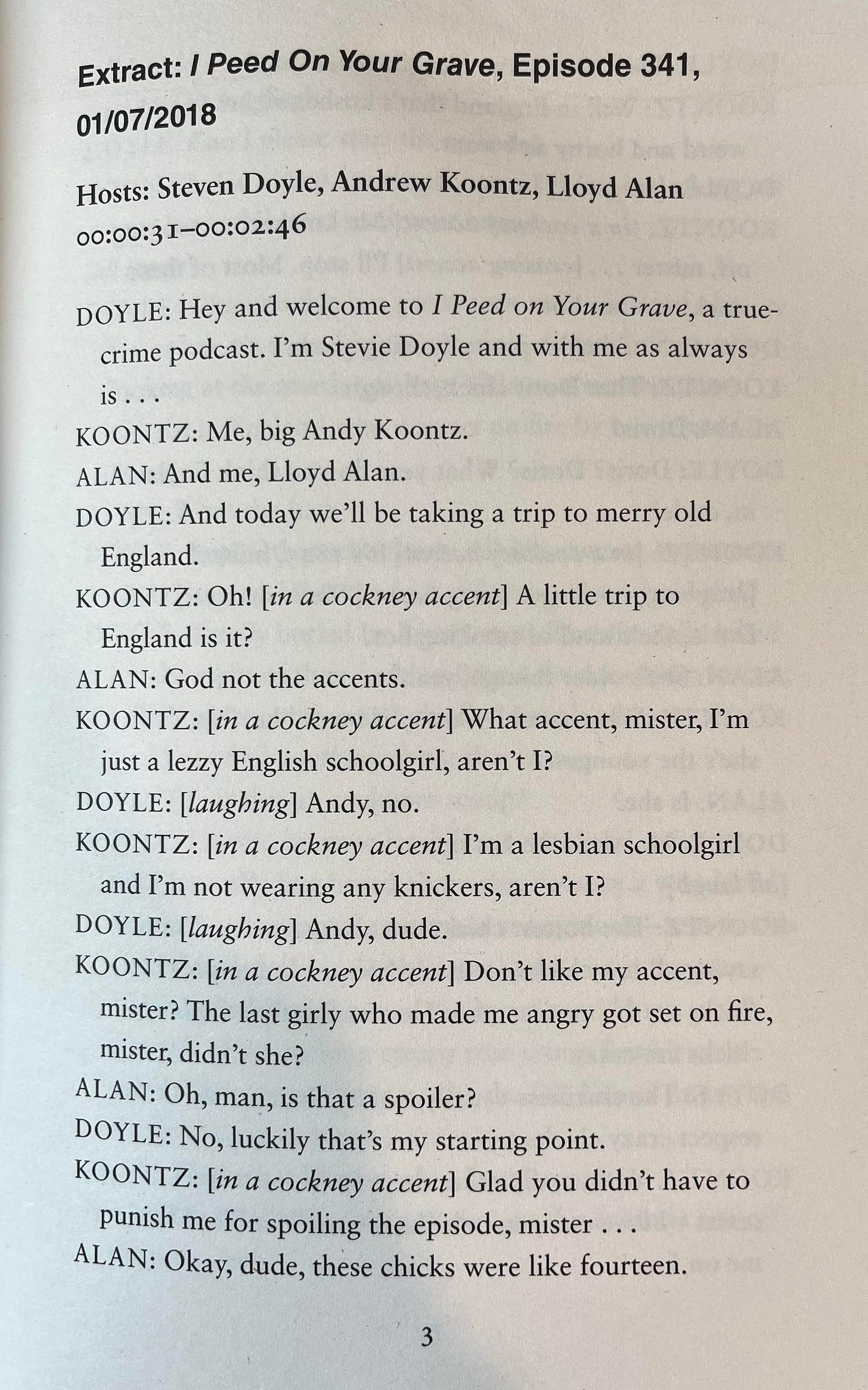

A major strength of the novel is Clark’s familiarity with her subjects, including the true crime industry and 2010s Internet culture. As well as the prose sections, Clark experiments with form by including excerpts from podcast episodes about Joni’s murder. In fact, after the preface, the first thing a reader encounters in the novel is an extract from a fictional podcast titled I Peed on Your Grave, wherein the hosts make light of the murder and tell homophobic and misogynistic jokes. Clark effectively examines the toxic masculinity of the podcast industry, influenced by Joe Rogan’s popular podcast, with its misogyny and rants about “cancel culture”. Later in the book, Clark includes an excerpt from a true crime podcast hosted by two women – in a nod to the plethora of such podcasts hosted by women, and the popularity of the true crime genre among women – who also treat Joni’s murder as just a story, and Violet as merely a character therein; they even wonder critically why she hasn’t attempted suicide. By creating these two very different podcasts that are ultimately both harmful and trivialise Joni’s death, Clark highlights the rot at the heart of the true crime podcast industry.

Clark’s exploration of 2010s Internet culture is just as strong as that of true crime. Four out of the five main characters are frequent users of the social media site Tumblr (an outsider female teenager in 2016 likely would be). We get a vivid image of their interests on Tumblr – Angelica participates in the musical theatre fandom side of the website, while Dolly and Violet’s interests are much darker. One of the novel’s plots involves Joni sending Angelica anonymous hate messages on Tumblr, which is a well-observed detail on Clark’s part; so much of the narrative revolves around bullying, and it is realistic for cyberbullying to occur between the characters too, given the time period, the ages of the characters, and the frequency of their use of social media.

Ultimately, the most effective (and unnerving) aspect of the characters’ relationships to the Internet is Dolly’s involvement in a form of serial killer fandom, following two school shooters (invented by Clark). Serial killer fandoms are a deeply disturbing corner of the Internet, but they do exist, especially among women, and including among teenage girls. Clark’s fictional fandom is vivid and detailed; since the murders took place at Cherry Creek High School, fans of the shooters – including Dolly – call themselves “creekers”. Despite Dolly’s assertion that she isn’t the kind of person to photoshop flower crowns onto the shooters, that she is fascinated with them in a more intellectual way, she does in fact treat these murderers as fictional characters, even writing fan fiction about them (excerpts from which Clark includes within the narrative). Clark goes into shocking detail about the “creekers”, which is even more discomfiting and affecting because it feels so realistic. Dolly is also part of a Discord server with other “creekers”, who realise in real-time that one of their own has tortured and murdered someone and wonder what it means for them. By the end of the novel, the reader is left wondering if Carelli himself is a form of “creeker” – he is morbidly fascinated with Joni’s murderers and finds them sympathetic, even if he doesn’t romanticise and infantilise them like the “creekers” do.

As imaginative and astute as Penance’s content is, Clark’s formal innovation is the best thing about this book. From the framing device to the prose sections, the podcast excerpts to the pieces of historical exposition, the text conversations to the message board deep dive into Tumblr posts and Discord messages, and finally to the interview/exposé on Carelli that concludes the book, Clark is fully committed to creating a complete picture of this story by using all of the techniques at her disposal, and thus crafts a novel that feels fresh and different. Penance is a fascinating intellectual exercise, in terms of how its framing device affects the act of reading, and its challenge to readers by mimicking that which it is critiquing. It’s also a thoughtful exploration of the stories we tell ourselves, and why.